—Rania Khalil

|

My friend Rania Khalil, who lives in Cairo, posted this note on Facebook on Wednesday, February 2, 2011, at 12:12 pm.  hello everyone! thank you so much for your love and concern, i feel it. I am not at home and just writing quickly. have not read my email as net has just returned. me and my family are fine, but friends of friends have died protesting and this will continue. please help spread the word that hosni mubarak is a dictator and nothing less. he has released undercover men to incite fighting in the peaceful protests i've seen with my own eyes. now he is creating a propaganda war, paying people to support him with signs that have been absent the entire time. he may curb protests but he will not quell what has begun! love to you all. more soon xoxo ps. will send photos! pps. please write american govt to end this regime. —Rania Khalil

0 Comments

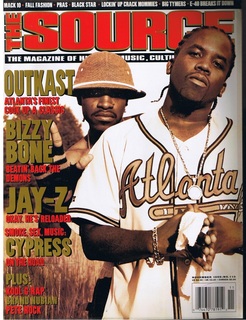

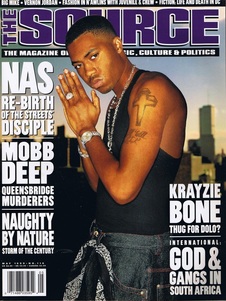

Socrates Since the Martin Luther King holiday last week, I’ve been musing over something Socrates said during his trial: “He who would really fight for justice, must do so as a private man, not in public, if he means to preserve his life, even for a short time.” If true, Socrates’ words mean Martin Luther King would have been assassinated even sooner had he been a public man, a politician, espousing the same views. In every age, men and women, public and private, have been rewarded with premature death for fighting for justice: Guevara, Lumumba, Gandhi, Nat Turner, Joan of Arc and, of course, Socrates himself.  "In the days ahead we must not consider it unpatriotic to raise certain basic questions about our national character. We must begin to ask, 'Why are there forty million poor people in a nation overflowing with such unbelievable affluence? Why has our nation placed itself in the position of being God's military agent on earth...? Why have we substituted the arrogant undertaking of policing the whole world for the high task of putting our own house in order?'" —Martin Luther King  The gunman who shot Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords through the skull, wounded 11 others and killed 6, chose bullets over words. This is the tragic culmination of a growing trend of insults, vandalism, personal threats and potential threats of armed revolt (from some Republican candidates). Culmination… Let us pray that this is the culmination and not just another stage in an ongoing escalation. But I don’t mean to make light of what happened to Giffords and the others in Tucson. Not at all. An article worth reading (if you haven't already): "Bloodshed Puts New Focus on Vitriol in Politics" (NYT) My Heavenly Father by Dana Crum This story was published in Gumbo: An Anthology of African American Writing in 2002 and in 64 Magazine in 2000.  It's the evening after I sinned against God, and the heat so bad it seem like somebody done wrapped a coat round my shoulders even though I don't need one. I start thinking about Hell. If I go there when I die, the Devil he gon' be waiting for me and he gon' poke me with that big pitchfork he got. I'm sitting on the steps of the porch, looking over at the houses across the street. Old people is out on their porches too, rocking in rocking chairs, fanning theyselves to keep cool. Every now and then one of 'em call across the street to somebody and ask how they doing. Them crickets done just started up their racket, and I'm thinking about what I did at church earlier today. That's when my grandma call me. "An-DRE!" she say, her voice getting high at the end. I put them quarters back in my pocket real fast like and look over my shoulder. "Mam?" The Odd Couple by Dana Crum This feature on OutKast was published in The Source in 1998.  View the PDF Healthy thighs and hips sway as honeys prance about in tight shorts. Leaning against cars, fellas lounge in long shorts and vivid jerseys--gold or red or luminous green. They sport matching caps and the latest Nikes and Filas. Dre, one half of OutKast, strolls through the crowd with his loping gait, wearing cut-off camouflage shorts, black soccer leggings and worn-down white Converse. He sports a football jersey too, but his is nondescript and netted and black. Under it is a white T-shirt. From beneath a tan safari hat he gazes out at the scene around him, his long braids dangling down his neck, the end of each capped with gleaming silver beads. No one else at the Organized Noize-Bad Boy-sponsored picnic is dressed like him. Does the crowd reject him? Is he an outcast amongst his fellow African-Americans? No. They give him love. Every few seconds another brother reaches out to shake his hand. Every few seconds another smiling sister approaches, holding a camera, asking if he'll take a picture with her. Not everyone who encounters Dre is so open-minded, though. The next day, at the Smokin' Grooves concert, flocks of fans greet him with homage, but one cat glares at him as though personally offended by his choice of clothes. Dre seems to notice. But he doesn't register a reaction. Hard Labor: Scholars Chronicle the Relationship of African Americans to Unions and the Industrialization of America by Dana Crum This round-up review was published in Black Issues Book Review in 2006.  Since Reconstruction, blacks’ unionization activity has taken two forms: attempts to integrate large white labor groups and attempts to build black unions. Early on, whichever form the activity took, the black workers behind it were fired, blacklisted and attacked by police, militia and mobs. White unions eventually began to integrate – but with all deliberate slowness. For African American laborers, faith in white unions alternated with distrust: Faith infused the Civil Rights Movement while Black Power was ingrained with distrust. During the latter period radical black unions emerged, and large integrated unions responded by opening leadership posts to moderate blacks and developing training and apprenticeship programs that gave some black workers the upward mobility they had long sought. Despite these changes, African American representation in union leadership, discrimination in hiring and promotion, and training for highly skilled jobs remain problem areas for organized labor. * * * Given how badly white unions treated black workers for most of the last 141 years, one of the opening sentences of Paul D. Moreno’s Black Americans and Organized Labor: A New History (Louisiana State University Press, January 2006) may come as a shock: “Today, black Americans are the demographic group most likely to belong to a labor union.” But according to Race and Labor Matters in the New U.S. Economy (Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., June 2006), edited by Manning Marable, Immanuel Ness and Joseph Wilson, unions have not done enough to save black people’s government jobs, which are being erased by the privatization of the public sector. To account for organized labor’s racist past, Professor Moreno for one proposes an economics-of-discrimination interpretation that examines the interplay of race, economics and law. Generally speaking, unions’ discriminatory practices cannot be blamed on employers, he argues. Employers do not normally “foment racial antagonism to keep the proletariat divided and weak.” Rather, they try “to pay as little as possible for labor, regardless of ethnicity” or race. It was usually white union members, not employers, who created and benefited from discrimination, Moreno adds. In Poor Workers’ Unions: Rebuilding Labor from Below (South End Press, January 2005), labor activist Vanessa Tait lays out the history of poor workers’ unions, which developed as an alternative to traditional labor groups (i.e., trade unions typically affiliated with the AFL-CIO). These alternative unions generally represent workers “at or below the poverty level” who toil in various trades and industries, including food service, home health care, domestic work, manufacturing and day labor. The groups range from civil rights—based job campaigns and welfare rights organizations to domestic workers’ unions and feminist labor groups. Most members are women and people of color. In the ’60s and early ’70s, Tait explains, the destitute created their own unions because trade unions “did not believe poor workers could be organized, either because of their fluctuating job status, or because of prejudices against their race, ethnicity, gender, poverty or immigration status.” The traditional labor movement, she concludes, has become “an institution protecting the organized few, instead of a broad social movement representing the interests of all workers.” * * * White sociologist Christine L. Williams goes deep cover as a low-wage retail worker at two national toy store chains in Inside Toyland: Working, Shopping, and Social Inequality (University of California Press, January 2006). Her findings are disturbing but not surprising: “Workers are sorted into jobs on the bases of race and gender, resulting in advantages for white men (and, to a lesser extent, white women) and blocked opportunities for racial/ethnic minority women and men.” Echoing Tait, Williams writes, “Historically, unions have not successfully redressed exclusionary hiring and promotion policies that favor whites over racial/ethnic minorities and men over women.” Black women’s labor during the antebellum period is the focus of Xiomara Santamarina’s Belabored Professions: Narratives of African American Working Womanhood (The University of North Carolina Press, October 2005). As Professor Santamarina notes, the paltry wages free black men were paid made it “absolutely necessary” that free black women work. Barred from most trades, they toiled as manual workers and domestic servants. Many felt these occupations degraded and degendered black women. Sojourner Truth, Eliza Potter, Harriet Wilson and Elizabeth Keckley disagreed and gave voice to their opinions in writing. In their autobiographies, which Santamarina thoroughly dissects, they described their labor as both valuable and respectable. Many black leaders bristled in response, believing racial advancement depended upon the creation of “male-headed households in which wives, daughters and sisters” remained home and raised children. Championing black women’s right to work rather than promoting the abolitionist agenda, the narratives Truth and company wrote diverged from the norms of the African American autobiographical tradition. * * * African American men were “at the center of the story of modernization in the South.” Such is the contention of William P. Jones in The Tribe of Black Ulysses: African American Lumber Workers in the Jim Crow South (University of Illinois Press, April 2005). The lumber industry between 1870 and 1910, he writes, “grew faster and employed more workers than any other industry in the southern United States.” “Whereas other industrial employers marginalized or excluded black workers, African American men formed the majority of the southern lumber workforce.…Before World War II, no other industry employed more African Americans.” In their fight for fair wages, black lumber workers—Professor Jones notes—received help from unions, with interracial harmony prevailing in some cases. Black Workers’ Struggle for Equality in Birmingham (University of Illinois Press, December 2004) also focuses on Southern black laborers. Edited by Horace Huntley and David Montgomery, the volume is the first in a projected series of books, each containing transcripts of interviews conducted by the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute’s Oral History Project. All interviewees are former civil rights activists who belonged to the city’s industrial workforce. As Professor Montgomery points out in the Introduction, “The unions were crisscrossed with networks, caucuses, and study groups organized by black workers. These informal organizations directly linked black union members to civil rights mobilizations based in churches and in community organizations,…[and] made the better known marches and court cases possible.” Matthew Whitaker’s Race Work: The Rise of Civil Rights in the Urban West (University of Nebraska Press, November 2005) reminds us that the South, the East and the Midwest were not the only theaters of activity in the Civil Rights Movement. The book assesses the movement in Phoenix as well as the achievements of two of the most important black activists of the post—World War II American West: Lincoln Ragsdale and his wife Eleanor. Whitaker notes that Ragsdale and a compatriot succeeded in desegregating many of the city’s main corporations in 1962, two years before the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission was even established. A review of Langston Hughes’ novel Tambourines to Glory by Dana Crum This book review was published in Black Issues Book Review in 2006.  Tambourines to Glory by Langston Hughes Harlem Moon, September 2006 $10.95, ISBN: 0-767-92327-8 Parts of this short novel are so funny I can imagine Langston Hughes pausing to laugh while writing it. In the book a black church starts on a Harlem street corner but soon moves into a thousand-seat theater. The day Crow-For-Day joins the congregation and converts, he confesses his many sins, one of which involved carrying a pistol. There in church he pulls out the gun, and congregants scream and faint. After walking down the aisle with it held over his head, he tosses it out the window to illustrate his conversion. But Crow-For-Day is merely a supporting cast member. Starring in this novel are Laura and Essie, two welfare recipients who establish the sidewalk church as a way to make money. Laura is devilishly funny. She frequently makes light of Christianity, distorting the Bible, giving its words lascivious, dissolute meanings. Can the Devil quote scripture? Indeed she can. Essie, on the other hand, is a true believer. Both women benefit financially from the church enterprise, but while Essie’s paramount concern is remaining true to God and helping the community, Laura wants only to wring as much cash as possible from the congregants. In this modern morality tale, Harlem Renaissance—luminary Langston Hughes pokes fun at the excesses of the black church, but never does he mock the black church itself. In fact, he celebrates the institution’s goodness, which Essie epitomizes. Hughes briskly ushers the narrative along in 36 very short chapters. Like poems, the chapters are compressed and have colorful titles. Though best known for his poetry, Hughes composed in several additional genres, including not just fiction but also drama, children’s literature and autobiography. Harlem Moon’s publication of Tambourines to Glory—this is its first appearance in trade paperback—means the more neglected of Hughes’ two novels may finally get the attention it has long deserved. The Friends We Leave Behind by Dana Crum This excerpt from my novel At the Cross was published in The Source in 1999.  View the PDF Sidney and Jamal said nothing to one another, the silence expanding between them, driving them further and further apart. And yet they continued to stand side by side, each, by way of a leg bent behind him, leaning against the old van that had long ago been abandoned in front of Sidney's building. Its headlights smashed, the driver's door hanging off its hinges and creaking with every breeze, the van bore all over its rusting sides graffiti—spindly crimson letters that spelt the names of the guys in Rob's crew. Jamal and his brother D'Angelo were represented there, a fact that so pricked and afflicted Sidney that he hastily ushered his mind down other avenues of thought. For most of the day and much of the evening, rain had pounded down on D.C., wetting but not washing the squalid streets of Carver Terrace; and even now, minutes after the maelstrom had ceased, a turbid rivulet still streamed against the curb, carrying with it cigarette butts, crack vials, golden leaves and ripped condom packages. The moisture had exasperated rather than quelled the heat so that now it was thick and heavy around Sidney, like an unwanted blanket. Soon the sky cracked and shattered again, except this time only a few falling shards made their way to earth. Clusters of them could be seen slanting down in the pale green cones of streetlamps. Sidney remained outside because the moisture felt cool and demulcent on his skin. He didn't know why Jamal, in his silence, remained, and he didn't ask. That Jamal would stand outside even in drizzling rain was all the more surprising given his comment over the phone earlier today. After Sidney noted the city was getting some much-needed rain, Jamal had muttered, "That's just God pissin' on us." Beneath the light from the streetlamps Jamal's grey Georgetown jersey glistened. His exposed arms, slender but muscular, were crossed, the dark skin freckled with raindrops. As he stared straight ahead, his thin mustache seemed even thinner over his thick unparting lips. Sidney felt pressured to speak, but all his thoughts led inevitably down the paths of college and D'Angelo, so he too remained silent. He wondered if D'Angelo had somehow passed on to Jamal his mercurial, at times aloof personality. Sidney had long believed this night, his last before leaving for college, would be a riotous one where the three of them would reminisce over old times and where he might finally yield to D'Angelo's insistence and for the first time really drink, quaff more than a couple of beers and maybe try Vodka or Jack Daniels or even Everclear. He'd thought he might even smoke some trees with Jamal, who would smoke until there was none left, who, with reddening eyes, would laugh at his own endless jokes even if no one else did. Sometimes Jamal would guffaw before he could even get a joke out. He could keep himself company for hours that way. And he was keeping himself company tonight, but with morbid brooding instead of weed-induced humor. Sidney had imagined himself drinking or smoking too much tonight to occupy his mind so he wouldn't think about what he knew D'Angelo and Jamal were thinking about. But instead only he and Jamal were there; and they were both pondering, though neither had admitted it, Sidney's impending departure. Their minds were further encumbered by an immeasurably worse event that had already occurred. As Sidney began to remember that event, as he began to remember what had happened to D'Angelo, he twisted a pantsleg of his jeans and stared at Jamal's turned-away face for help. He longed to rip out that huge slab of his cerebrum that held memories. Instead of setting them free to fly away like wild and whirling birds, his greedy brain clutched the most abhorrent memories tighter, as if for its very sustenance. Nothing Can Remain Unchanged by Dana Crum This excerpt from my novel At the Cross was published in Bronx Biannual: The Journal of Urbane Urban Literature (issue no. 1) in 2006.  Sidney had just graduated from high school; and beyond the gleaming limestone columns of D.C.'s Constitution Hall, people he didn't know were commending him for his valedictory. His speech also elicited reactions from his friends. Jamal patted him on the back. Jamal's brother, D'Angelo, looked away, then muttered that he was going to get the car. Sidney watched his brawny frame, clad in khakis and a burgundy knit top, recede into the throng, where black caps and gowns abounded. The darkness swelled with heat, and many graduates began to step out of their gowns. But Sidney kept his on. "How's ya moms?" Jamal asked. "She's doing better. She'll be home soon." "I know she feel bad about missing this." "Yeah." Before graduation Sidney had gone to the hospital to see her. He strode through the halls and through the strong smell of Lysol, and once inside her room he sat in the orange plastic chair beside her bed. They talked for a while. Then she asked him to read his speech. As he read in the weak glow of the single working light, she lay with the bleached sheets drawn up over her short rotund body. Her eyes glistened wet. "I sure wish I could be there," she said when he was done. She smiled and touched his hand. "It's beautiful." His gown fluttering in the useless breeze, he realized there would have been a scene if she had been able to make it: she would have refused to ride in the same car with D'Angelo and Jamal. |

Dana's Blog

Thanks for stopping by. I'm glad you could make it. Categories

All

Archives

May 2016

Favorite BlogsProse Wizard |