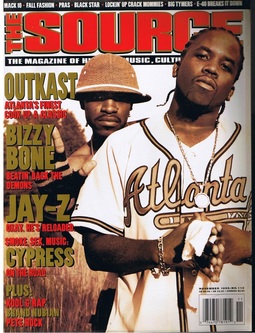

The Odd Couple

Written by Dana Crum, this feature on OutKast appeared in the Nov. 1998 issue of The Source.

View the PDF

Healthy thighs and hips sway as honeys prance about in tight shorts. Leaning against cars, fellas lounge in long shorts and vivid jerseys--gold or red or luminous green. They sport matching caps and the latest Nikes and Filas.

Dre, one half of OutKast, strolls through the crowd with his loping gait, wearing cut-off camouflage shorts, black soccer leggings and worn-down white Converse. He sports a football jersey too, but his is nondescript and netted and black. Under it is a white T-shirt. From beneath a tan safari hat he gazes out at the scene around him, his long braids dangling down his neck, the end of each capped with gleaming silver beads.

No one else at the Organized Noize-Bad Boy-sponsored picnic is dressed like him. Does the crowd reject him? Is he an outcast amongst his fellow African-Americans? No. They give him love. Every few seconds another brother reaches out to shake his hand. Every few seconds another smiling sister approaches, holding a camera, asking if he'll take a picture with her.

Not everyone who encounters Dre is so open-minded, though. The next day, at the Smokin' Grooves concert, flocks of fans greet him with homage, but one cat glares at him as though personally offended by his choice of clothes. Dre seems to notice. But he doesn't register a reaction.

Dre, one half of OutKast, strolls through the crowd with his loping gait, wearing cut-off camouflage shorts, black soccer leggings and worn-down white Converse. He sports a football jersey too, but his is nondescript and netted and black. Under it is a white T-shirt. From beneath a tan safari hat he gazes out at the scene around him, his long braids dangling down his neck, the end of each capped with gleaming silver beads.

No one else at the Organized Noize-Bad Boy-sponsored picnic is dressed like him. Does the crowd reject him? Is he an outcast amongst his fellow African-Americans? No. They give him love. Every few seconds another brother reaches out to shake his hand. Every few seconds another smiling sister approaches, holding a camera, asking if he'll take a picture with her.

Not everyone who encounters Dre is so open-minded, though. The next day, at the Smokin' Grooves concert, flocks of fans greet him with homage, but one cat glares at him as though personally offended by his choice of clothes. Dre seems to notice. But he doesn't register a reaction.

***

In the two years that he and partner in rhyme Big Boi have spent working on their third and latest album Aquemini, Dre has grown accustomed to the occasional ambivalence and disapproval elicited by his increasingly eccentric attire."A lotta people may look at me and be like, 'Man, this nigga's crazy. Man, fuck this, nigga. I ain't listenin' to this nigga shit. This nigga on some wild shit.' But, I mean, really, it's not about me. It's about the music, man. If you like the music, man, jam to it. If you don't like me, just say, 'Okay, he on some other shit.' You'know'I'msayin'?"

Whether Dre is talking to you in person or rhyming through your Pioneer speakers, the Southern drawl and twang with which he speaks slang puts you immediately at ease. While navigating his forest-green Landcruiser through Atlanta's sprawling, many-laned expressways, which coil about in ramps and swollen overpasses, he describes his style of dress as "some funk, wild-out shit."

But don't think he's trying to pass as George Clinton's little nephew. "Nah, I mean, it's right now. And I don't want people to be like, 'This nigga tryin' to do some George Clinton shit.' 'Cause I'm not. I love what George did. And, I mean, I studied them niggas 'cause I love they music. But I'm not tryin' to imitate nothin' they doin'. I'm doin' some Dre shit, some Dre 1998 wild-out shit."

The "they" he speaks of includes James Brown and Parliament. And when he says he studied them, he means it. At the moment he's perusing a biography on George Clinton. Though his mode of dress is funk-influenced today, tomorrow it may be completely different. "Tomorrow I'll turn around, and I may throw on a goddamn bow tie, some slacks. I'm an artist, man, youknow'I'msayin'? So I'm gon' change. What I'm sayin' is never peg me. I mean, you can't just say Dre is one way. So what I really want people to say is 'That nigga might do anything, man.' And that's true."

Dre has gone through a metamorphosis, but it's not his first and it won't be his last. Though his steez has always been subject to change, his past metamorphoses weren't nearly as drastic. The opportunity music has given him to express himself has bolstered his confidence and drawn out hitherto hidden facets of his personality.

"I done changed totally," he says. "But inside I'm the same person." A contradiction? Nah, sun, a paradox. Dre is a chameleon. In other words, he's a Gemini, a scrap of information that explains more than any metaphor could. If you know any Geminis, you understand what I'm talking about.

As the glittering glass skyscrapers and rigid stone edifices of downtown Atlanta scroll past my window, Dre imagines life if his mutability were suddenly suppressed. "I'd die if I had to stay one way. Geminis get bored very fast."

Geminis can be enigmatic, but they have helped make music the life-affirming, multi-faceted art form it is today (Imagine hip-hop without the contributions of Biggie Smalls and Tupac, pop without the Artist Formerly Known as Prince.). Dre has made his share of contributions, whatever he's wearing on a given day.

Whether Dre is talking to you in person or rhyming through your Pioneer speakers, the Southern drawl and twang with which he speaks slang puts you immediately at ease. While navigating his forest-green Landcruiser through Atlanta's sprawling, many-laned expressways, which coil about in ramps and swollen overpasses, he describes his style of dress as "some funk, wild-out shit."

But don't think he's trying to pass as George Clinton's little nephew. "Nah, I mean, it's right now. And I don't want people to be like, 'This nigga tryin' to do some George Clinton shit.' 'Cause I'm not. I love what George did. And, I mean, I studied them niggas 'cause I love they music. But I'm not tryin' to imitate nothin' they doin'. I'm doin' some Dre shit, some Dre 1998 wild-out shit."

The "they" he speaks of includes James Brown and Parliament. And when he says he studied them, he means it. At the moment he's perusing a biography on George Clinton. Though his mode of dress is funk-influenced today, tomorrow it may be completely different. "Tomorrow I'll turn around, and I may throw on a goddamn bow tie, some slacks. I'm an artist, man, youknow'I'msayin'? So I'm gon' change. What I'm sayin' is never peg me. I mean, you can't just say Dre is one way. So what I really want people to say is 'That nigga might do anything, man.' And that's true."

Dre has gone through a metamorphosis, but it's not his first and it won't be his last. Though his steez has always been subject to change, his past metamorphoses weren't nearly as drastic. The opportunity music has given him to express himself has bolstered his confidence and drawn out hitherto hidden facets of his personality.

"I done changed totally," he says. "But inside I'm the same person." A contradiction? Nah, sun, a paradox. Dre is a chameleon. In other words, he's a Gemini, a scrap of information that explains more than any metaphor could. If you know any Geminis, you understand what I'm talking about.

As the glittering glass skyscrapers and rigid stone edifices of downtown Atlanta scroll past my window, Dre imagines life if his mutability were suddenly suppressed. "I'd die if I had to stay one way. Geminis get bored very fast."

Geminis can be enigmatic, but they have helped make music the life-affirming, multi-faceted art form it is today (Imagine hip-hop without the contributions of Biggie Smalls and Tupac, pop without the Artist Formerly Known as Prince.). Dre has made his share of contributions, whatever he's wearing on a given day.

***

What is true of Dre is true of the music he and Big Boi create together. It's drastically different from other hip-hop, but it's undeniably hip-hop. The music changes from album to album, but it always has that recognizable OutKast sound (This time around the music is as funked-out as Dre's clothes.). And though many dig the music, not everyone does. But then this is true of all groups.

What is not true of every group is a sizable fan base. OutKast has maintained such a following despite the risks it takes. Though its experiments are consistently successful and groundbreaking, some fans abandoned the group when the second album ATLiens blasted the hip-hop populace into outer space at the speed of light. Many were expecting another dose of the funk characteristic of the group's debut Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik.

Despite the slight exodus in the OutKast fan club, the second album sold a million and a half copies, five hundred thousand more than the first, an accomplishment that shows Dre and Big Boi gained some followers even while losing others. Aquemini will not only maintain their fans, new and old; it will hold sway over those who were afraid to follow when asked to bravely go where no man had gone before.

As always, OutKast to a large extent employs live instruments. Organized Noize has been doing the production since day one, but after Cadillacmuzik Dre and Big Boi, who know a great deal about music in their own right, began assuming greater responsibility for the tracks over which they rhyme. Of the fifteen cuts on the new album, they produced seven.

The LP, Dre says, is a midpoint between the first two albums and could have served as the second. Clad in a red football jersey and a matching fuzzy Kango that covers his braids, Big Boi elaborates. "This album is a mixture between the music on the first album and the lyrical styles of the second. It's like now we done mastered our style so much that we can flip it any kind of way we wanna flip it."

However, in revisiting previous musical and lyrical formats, they were sure, he says, to update them and sometimes subvert them altogether. Case in point: for those of you who fiend for that unadulterated funk OutKast came with on album one, there are songs like "Slump," a jam complete with crooning and a groove that simply moves. But then there's also "Rosa Parks," which of all the songs on the album probably best demonstrates the group's willingness to take chances. The song is daring but not reckless. Its folk-music underpinnings culminate in a wailing harmonica interlude.

"We step into some different realms [from] what's like normal hip-hop," Dre says. To understand why their artistic creations are so eclectic, you must first understand that in their respective households a mélange of musical genres was played. As adults they even explored genres they hadn't been exposed to growing up. Consequently, their musical sensibility is a kettle-cooked stew full of huge chunks of funk and hip-hop, but further flavored by a wholesome, spicy mishmash of soul, reggae, rock, calypso, blues and classical.

Friend and filmmaker Brian Barber recalls the first time Dre and Big ladled him out a steaming-hot serving from the new album. "I was like, 'Where y'all tryin' to go wit' it?' And I remember them sayin' that they can't do the last album. They gotta reinvent themselves every time they come out, 'know'I'msayin'? If you don't reinvent yourself as an artist, you end up sayin' the same thing you done already said."

What is not true of every group is a sizable fan base. OutKast has maintained such a following despite the risks it takes. Though its experiments are consistently successful and groundbreaking, some fans abandoned the group when the second album ATLiens blasted the hip-hop populace into outer space at the speed of light. Many were expecting another dose of the funk characteristic of the group's debut Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik.

Despite the slight exodus in the OutKast fan club, the second album sold a million and a half copies, five hundred thousand more than the first, an accomplishment that shows Dre and Big Boi gained some followers even while losing others. Aquemini will not only maintain their fans, new and old; it will hold sway over those who were afraid to follow when asked to bravely go where no man had gone before.

As always, OutKast to a large extent employs live instruments. Organized Noize has been doing the production since day one, but after Cadillacmuzik Dre and Big Boi, who know a great deal about music in their own right, began assuming greater responsibility for the tracks over which they rhyme. Of the fifteen cuts on the new album, they produced seven.

The LP, Dre says, is a midpoint between the first two albums and could have served as the second. Clad in a red football jersey and a matching fuzzy Kango that covers his braids, Big Boi elaborates. "This album is a mixture between the music on the first album and the lyrical styles of the second. It's like now we done mastered our style so much that we can flip it any kind of way we wanna flip it."

However, in revisiting previous musical and lyrical formats, they were sure, he says, to update them and sometimes subvert them altogether. Case in point: for those of you who fiend for that unadulterated funk OutKast came with on album one, there are songs like "Slump," a jam complete with crooning and a groove that simply moves. But then there's also "Rosa Parks," which of all the songs on the album probably best demonstrates the group's willingness to take chances. The song is daring but not reckless. Its folk-music underpinnings culminate in a wailing harmonica interlude.

"We step into some different realms [from] what's like normal hip-hop," Dre says. To understand why their artistic creations are so eclectic, you must first understand that in their respective households a mélange of musical genres was played. As adults they even explored genres they hadn't been exposed to growing up. Consequently, their musical sensibility is a kettle-cooked stew full of huge chunks of funk and hip-hop, but further flavored by a wholesome, spicy mishmash of soul, reggae, rock, calypso, blues and classical.

Friend and filmmaker Brian Barber recalls the first time Dre and Big ladled him out a steaming-hot serving from the new album. "I was like, 'Where y'all tryin' to go wit' it?' And I remember them sayin' that they can't do the last album. They gotta reinvent themselves every time they come out, 'know'I'msayin'? If you don't reinvent yourself as an artist, you end up sayin' the same thing you done already said."

***

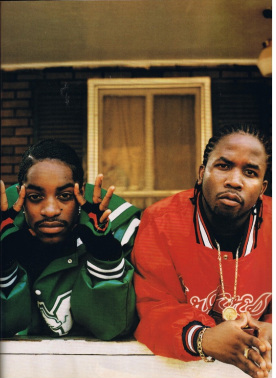

Dre and Big Boi's continual transmutations keep them from sounding too much like themselves. Their old selves, that is. Most significant, of course, is how different the two-man crew sounds from other hip-hop groups. Their music rises out of the din, leaving you entranced. "OutKast"--as they use it to refer to themselves--is synonymous with someone who insists upon individuality at all costs. But if Dre and Big Boi are true outkasts, it stands to reason that they are different not only from other groups but also from one another.

And different they are. So different that during the time since ATLiens dropped, a rumor was spread across Atlanta that the two were parting ways. People behaved as though Dre were indeed from outer space and wondered how Big Boi could possibly work with him, let alone hang with him.

In his gruff voice, Big Boi vents, "Everybody wanna think, 'They breakin' up. Oh, [they] so different.' They mad, man, 'cause, I mean, they can't figure it out yet. How can we still do [what we do]--niggas bein' so different? I smoke. He don't smoke. I go to strip clubs. He don't go to strip clubs. He used to, youknowhatI'msayin'?" Big Boi notes, alluding to the lifestyle shift that coincided with the shift in Dre's attire. "I drink. He don't drink. Like that. They can't comprehend that. I mean, it's just homeboy shit. Whatever people wanna do is their own right, youknow'I'msayin'? Like how he dress, how I dress. Whatever. I mean, that's individualism. And that's what OutKast is all about."

When Dre's lifestyle changed, their friendship didn't. After all, they were used to negotiating differences in their personalities, something they'd been doing since the day they met. In terms of lyrical content, Big Boi is more street while Dre is more spiritual and conscious. Dre, an only child, is a self-described recluse who only occasionally needs companionship while Big Boi, surrounded by brothers and sisters as a child, always has people around him. Though the former lives in a house by himself, the latter had siblings and cousins move in to his house to keep him, his girlfriend and his daughter company. Away from the homestead, Big Boi roams Atlanta with a phalanx of partners.

Dre, on the other hand, hits the movies by himself and waits until the last show to avoid the crowd. Sometimes friends and acquaintances will spot him and ask why he's alone. He tells them he does this all the time, as if nothing's wrong. And nothing is wrong. Solitude soothes his soul. Even when hanging with friends, he from time to time pulls away from the group and seizes a few precious moments to retreat inside himself.

Heads who rumored that OutKast was breaking up were aware of all these differences between Dre and Big Boi, but no difference preoccupied them more than the stark contrast in how the two dress. In their provincial world view, Dre's eccentric attire could only mean either of two things. He was acting like a white boy. Or he was gay. After they marinated over one hypothesis for a while, their opinion swung in the other direction and they stepped to Big Boi with questions: "I mean, what's wrong wit' him? You the cool one. That nigga gay or somethin'?"

And different they are. So different that during the time since ATLiens dropped, a rumor was spread across Atlanta that the two were parting ways. People behaved as though Dre were indeed from outer space and wondered how Big Boi could possibly work with him, let alone hang with him.

In his gruff voice, Big Boi vents, "Everybody wanna think, 'They breakin' up. Oh, [they] so different.' They mad, man, 'cause, I mean, they can't figure it out yet. How can we still do [what we do]--niggas bein' so different? I smoke. He don't smoke. I go to strip clubs. He don't go to strip clubs. He used to, youknowhatI'msayin'?" Big Boi notes, alluding to the lifestyle shift that coincided with the shift in Dre's attire. "I drink. He don't drink. Like that. They can't comprehend that. I mean, it's just homeboy shit. Whatever people wanna do is their own right, youknow'I'msayin'? Like how he dress, how I dress. Whatever. I mean, that's individualism. And that's what OutKast is all about."

When Dre's lifestyle changed, their friendship didn't. After all, they were used to negotiating differences in their personalities, something they'd been doing since the day they met. In terms of lyrical content, Big Boi is more street while Dre is more spiritual and conscious. Dre, an only child, is a self-described recluse who only occasionally needs companionship while Big Boi, surrounded by brothers and sisters as a child, always has people around him. Though the former lives in a house by himself, the latter had siblings and cousins move in to his house to keep him, his girlfriend and his daughter company. Away from the homestead, Big Boi roams Atlanta with a phalanx of partners.

Dre, on the other hand, hits the movies by himself and waits until the last show to avoid the crowd. Sometimes friends and acquaintances will spot him and ask why he's alone. He tells them he does this all the time, as if nothing's wrong. And nothing is wrong. Solitude soothes his soul. Even when hanging with friends, he from time to time pulls away from the group and seizes a few precious moments to retreat inside himself.

Heads who rumored that OutKast was breaking up were aware of all these differences between Dre and Big Boi, but no difference preoccupied them more than the stark contrast in how the two dress. In their provincial world view, Dre's eccentric attire could only mean either of two things. He was acting like a white boy. Or he was gay. After they marinated over one hypothesis for a while, their opinion swung in the other direction and they stepped to Big Boi with questions: "I mean, what's wrong wit' him? You the cool one. That nigga gay or somethin'?"