The Friends We Leave Behind

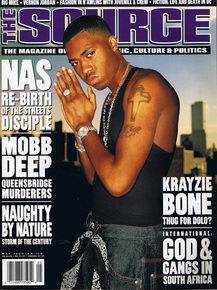

This excerpt from Dana Crum's novel At the Cross appeared in the May 1999 issue of The Source.

View the PDF

Sidney and Jamal said nothing to one another, the silence expanding between them, driving them further and further apart. And yet they continued to stand side by side, each, by way of a leg bent behind him, leaning against the old van that had long ago been abandoned in front of Sidney's building. Its headlights smashed, the driver's door hanging off its hinges and creaking with every breeze, the van bore all over its rusting sides graffiti—spindly crimson letters that spelt the names of the guys in Rob's crew. Jamal and his brother D'Angelo were represented there, a fact that so pricked and afflicted Sidney that he hastily ushered his mind down other avenues of thought.

For most of the day and much of the evening, rain had pounded down on D.C., wetting but not washing the squalid streets of Carver Terrace; and even now, minutes after the maelstrom had ceased, a turbid rivulet still streamed against the curb, carrying with it cigarette butts, crack vials, golden leaves and ripped condom packages. The moisture had exasperated rather than quelled the heat so that now it was thick and heavy around Sidney, like an unwanted blanket. Soon the sky cracked and shattered again, except this time only a few falling shards made their way to earth. Clusters of them could be seen slanting down in the pale green cones of streetlamps. Sidney remained outside because the moisture felt cool and demulcent on his skin. He didn't know why Jamal, in his silence, remained, and he didn't ask. That Jamal would stand outside even in drizzling rain was all the more surprising given his comment over the phone earlier today. After Sidney noted the city was getting some much-needed rain, Jamal had muttered, "That's just God pissin' on us."

Beneath the light from the streetlamps Jamal's grey Georgetown jersey glistened. His exposed arms, slender but muscular, were crossed, the dark skin freckled with raindrops. As he stared straight ahead, his thin mustache seemed even thinner over his thick unparting lips. Sidney felt pressured to speak, but all his thoughts led inevitably down the paths of college and D'Angelo, so he too remained silent. He wondered if D'Angelo had somehow passed on to Jamal his mercurial, at times aloof personality. Sidney had long believed this night, his last before leaving for college, would be a riotous one where the three of them would reminisce over old times and where he might finally yield to D'Angelo's insistence and for the first time really drink, quaff more than a couple of beers and maybe try Vodka or Jack Daniels or even Everclear. He'd thought he might even smoke some trees with Jamal, who would smoke until there was none left, who, with reddening eyes, would laugh at his own endless jokes even if no one else did. Sometimes Jamal would guffaw before he could even get a joke out. He could keep himself company for hours that way. And he was keeping himself company tonight, but with morbid brooding instead of weed-induced humor. Sidney had imagined himself drinking or smoking too much tonight to occupy his mind so he wouldn't think about what he knew D'Angelo and Jamal were thinking about. But instead only he and Jamal were there; and they were both pondering, though neither had admitted it, Sidney's impending departure. Their minds were further encumbered by an immeasurably worse event that had already occurred.

As Sidney began to remember that event, as he began to remember what had happened to D'Angelo, he twisted a pantsleg of his jeans and stared at Jamal's turned-away face for help. He longed to rip out that huge slab of his cerebrum that held memories. Instead of setting them free to fly away like wild and whirling birds, his greedy brain clutched the most abhorrent memories tighter, as if for its very sustenance.

From some apartment window far above came the wailing winding sound of "Self-Destruction." Since the song's debut months ago, how many times had he played it for D'Angelo and Jamal with the naïve hope of persuading them to stop selling drugs?

Through blurring vision he gazed at the strip near the foot of the hill. There tiny figures shifted against the darkness, like harmless images in a shoot-'em-up video game. He'd looked in their direction many times tonight. Jamal hadn't, not even once, but Sidney sensed he too knew Rob and his crew were watching them, their hands concealed in jacket pockets, tightening into fists or tracing the cold edges of gun handles.

Swiftly, Sidney wiped his eyes, but when he looked over, Jamal was glaring at him.

Jamal turned away, displaced his weight onto his other leg. "It's a good thing yo' moms ain't goin' nowhere," he said. "Otherwise, I wouldn't never see yo' ass again."

The realization that Jamal was right struck Sidney, physically struck him, like a blow to the chest. The single force strong enough to year after year pull him back to this street, this place of blunted dreams and greed-driven schemes, was his mom.

He let his eyes drift over the neighborhood. Streetlamps threw long slippery streaks of light onto the street, a slab of asphalt slick with rain. Maryland Avenue, with the glare from the wet street and the watery glow of the streetlamps themselves, was unusually bright tonight. It was a brightness heightened by the dark turbid sky and by the dark forms of crackheads. Scrawny, disheveled, their feet slow but their eyes quick, they drifted in and out of shadows, disappearing then reappearing like faint taunting ghosts. From end to end the street had been invaded by streaks and orbs of light, by men and women dying slowly and willfully. And at the foot of the hill stood boys who helped them do so, not out of malice or out of some twisted euthanasia, but out of simple unadulterated greed. Even if it were snowing at three in the morning, Rob's crew would be on the corner, selling them rocks.

All of a sudden, at first one by one and then two and three at a time, the crackheads began crossing the street and flooding the strip with their fleshless forms, coming through like cars at a gas station. The members of Rob's crew at first hesitated. Then, glancing from time to time at Sidney and Jamal, they began snatching wrinkled bills from the crackheads' hands and dropping red-capped vials into their rusty open palms. Sidney didn't know what made the crackheads swoop down all of a sudden like filthy pigeons on bits of bird seed. All he knew was that while he watched them, watched them shift back and forth, stride up the hill, down the hill, around the corner and into buildings, he was nearly stricken with vertigo and had to close his eyes to keep the street from spinning into a wet, confounding blur.

Naming this place, this lake of fire atop asphalt, after the inventor George Washington Carver, Sidney decided, had been nothing short of sacrilege. Now that D'Angelo was gone, no one but Sidney's mom could give him strong enough reason to return. And what if she were to move? He wanted to believe he'd come back to visit Jamal, but would he? No. He would ask Jamal to meet him somewhere instead. Somewhere like Georgetown.

"I would come back," he said, telling himself this statement was true, in a manner of speaking.

Jamal blew air through his teeth. "Yeah, right. But a'ight, let's just say you would. Let's just say that. You come back maybe a few times when you on break and shit, but after a while, after a few months, you wouldn't no more. 'Cause sooner or later it would hit you that you ain't gotta come back." His voice grew subdued. "Shit, if I could get out, I would too."

"You can get out."

In Jamal's eyes flames of aggravation blazed into conflagrations of hatred. Moments passed and the fires smoldered, then died altogether. Jamal looked away, spat on the sidewalk. "I can't get out," he whispered, as if to himself.

"You can!" Sidney yelled, clutching his arm. "I'm telling you, you can!"

Jamal shoved him away. "Would you shut the fuck up? I'm so sick of you sayin' this stupid shit. I can just leave. Fuck kinda shit is that? He was my motherfuckin' brother!"

So loud were Jamal's shouts that Sidney worried Rob's crew had heard. But when he looked their way, they were still making sales, revealing no indication of having heard a word. He was still watching them when he said: "You know if you try anything. . . they'll kill you."

"Look, mind ya business. See, that's the thing. You know 'bout books and shit. You got into Princeton and won scholarships and all that. But right now? Right now you talkin' 'bout shit you don't know a goddamn thing about!"

"Fuck you mean I don't know about it? I was there when it happened. Were you? No. I saw it. He died saving my life. I gotta live with that, and yet I'm trying to move on. Why can't you?"

Jamal stepped away from the van, and suddenly the numbers on his damp jersey were at Sidney's eyes. "You sayin' I should just walk away? And do nothin'? Nigga, I could punch you in yo' face for that."

Sidney clenched his fists, clenched them so tightly he could feel the thin bones in his hands. For a moment he thought he could do it—punch Jamal in the stomach and kick him and drag him to New Jersey tomorrow morning—but then the desire subsided as rapidly as it had surged when Jamal turned away and Sidney recognized, with an aching emptiness, his inability to overpower Jamal physically or mentally. Jamal would die in this neighborhood, and there was nothing Sidney could do.

He could feel himself being dragged down into the reddish whirlpool of what happened to D’Angelo that night last week. He swam, struggling with every tendon in his soul to resist the pull, to dwell on a more benevolent thought, an amusing one. He'd nearly reached the whirlpool's outer lip, but just then he felt himself swallowed, pulled under, and he was there again, with D'Angelo, the two of them striding through pale pools of light spilt by streetlamps. D'Angelo, for some unrevealed reason, was rushing down the hill toward his car, and it was all Sidney could do to keep up. It was all Sidney could do to get responses of any kind from him, let alone answers to questions. Then something struck D'Angelo still, left him rooted to the concrete slab on which they stood.

"What's wrong?" Sidney asked.

D'Angelo said nothing, his eyes—light brown like his skin and lips—fixed on something, their stare accentuated beneath the brim of his green Celtics cap.

"What is it?" Sidney asked. He followed D'Angelo's eyes to the redbrick buildings on the corner up ahead and saw nothing of significance, but what he heard was the roaring of an engine. Hidden from view, a car was racing up the side street toward them.

In a cloud of dust and din a black Maxima fishtailed around the corner, sped up the hill and screeched to a halt in the middle of the street, the engine still running. The car belonged to Junebug, one of the guys in Rob's crew.

For most of the day and much of the evening, rain had pounded down on D.C., wetting but not washing the squalid streets of Carver Terrace; and even now, minutes after the maelstrom had ceased, a turbid rivulet still streamed against the curb, carrying with it cigarette butts, crack vials, golden leaves and ripped condom packages. The moisture had exasperated rather than quelled the heat so that now it was thick and heavy around Sidney, like an unwanted blanket. Soon the sky cracked and shattered again, except this time only a few falling shards made their way to earth. Clusters of them could be seen slanting down in the pale green cones of streetlamps. Sidney remained outside because the moisture felt cool and demulcent on his skin. He didn't know why Jamal, in his silence, remained, and he didn't ask. That Jamal would stand outside even in drizzling rain was all the more surprising given his comment over the phone earlier today. After Sidney noted the city was getting some much-needed rain, Jamal had muttered, "That's just God pissin' on us."

Beneath the light from the streetlamps Jamal's grey Georgetown jersey glistened. His exposed arms, slender but muscular, were crossed, the dark skin freckled with raindrops. As he stared straight ahead, his thin mustache seemed even thinner over his thick unparting lips. Sidney felt pressured to speak, but all his thoughts led inevitably down the paths of college and D'Angelo, so he too remained silent. He wondered if D'Angelo had somehow passed on to Jamal his mercurial, at times aloof personality. Sidney had long believed this night, his last before leaving for college, would be a riotous one where the three of them would reminisce over old times and where he might finally yield to D'Angelo's insistence and for the first time really drink, quaff more than a couple of beers and maybe try Vodka or Jack Daniels or even Everclear. He'd thought he might even smoke some trees with Jamal, who would smoke until there was none left, who, with reddening eyes, would laugh at his own endless jokes even if no one else did. Sometimes Jamal would guffaw before he could even get a joke out. He could keep himself company for hours that way. And he was keeping himself company tonight, but with morbid brooding instead of weed-induced humor. Sidney had imagined himself drinking or smoking too much tonight to occupy his mind so he wouldn't think about what he knew D'Angelo and Jamal were thinking about. But instead only he and Jamal were there; and they were both pondering, though neither had admitted it, Sidney's impending departure. Their minds were further encumbered by an immeasurably worse event that had already occurred.

As Sidney began to remember that event, as he began to remember what had happened to D'Angelo, he twisted a pantsleg of his jeans and stared at Jamal's turned-away face for help. He longed to rip out that huge slab of his cerebrum that held memories. Instead of setting them free to fly away like wild and whirling birds, his greedy brain clutched the most abhorrent memories tighter, as if for its very sustenance.

From some apartment window far above came the wailing winding sound of "Self-Destruction." Since the song's debut months ago, how many times had he played it for D'Angelo and Jamal with the naïve hope of persuading them to stop selling drugs?

Through blurring vision he gazed at the strip near the foot of the hill. There tiny figures shifted against the darkness, like harmless images in a shoot-'em-up video game. He'd looked in their direction many times tonight. Jamal hadn't, not even once, but Sidney sensed he too knew Rob and his crew were watching them, their hands concealed in jacket pockets, tightening into fists or tracing the cold edges of gun handles.

Swiftly, Sidney wiped his eyes, but when he looked over, Jamal was glaring at him.

Jamal turned away, displaced his weight onto his other leg. "It's a good thing yo' moms ain't goin' nowhere," he said. "Otherwise, I wouldn't never see yo' ass again."

The realization that Jamal was right struck Sidney, physically struck him, like a blow to the chest. The single force strong enough to year after year pull him back to this street, this place of blunted dreams and greed-driven schemes, was his mom.

He let his eyes drift over the neighborhood. Streetlamps threw long slippery streaks of light onto the street, a slab of asphalt slick with rain. Maryland Avenue, with the glare from the wet street and the watery glow of the streetlamps themselves, was unusually bright tonight. It was a brightness heightened by the dark turbid sky and by the dark forms of crackheads. Scrawny, disheveled, their feet slow but their eyes quick, they drifted in and out of shadows, disappearing then reappearing like faint taunting ghosts. From end to end the street had been invaded by streaks and orbs of light, by men and women dying slowly and willfully. And at the foot of the hill stood boys who helped them do so, not out of malice or out of some twisted euthanasia, but out of simple unadulterated greed. Even if it were snowing at three in the morning, Rob's crew would be on the corner, selling them rocks.

All of a sudden, at first one by one and then two and three at a time, the crackheads began crossing the street and flooding the strip with their fleshless forms, coming through like cars at a gas station. The members of Rob's crew at first hesitated. Then, glancing from time to time at Sidney and Jamal, they began snatching wrinkled bills from the crackheads' hands and dropping red-capped vials into their rusty open palms. Sidney didn't know what made the crackheads swoop down all of a sudden like filthy pigeons on bits of bird seed. All he knew was that while he watched them, watched them shift back and forth, stride up the hill, down the hill, around the corner and into buildings, he was nearly stricken with vertigo and had to close his eyes to keep the street from spinning into a wet, confounding blur.

Naming this place, this lake of fire atop asphalt, after the inventor George Washington Carver, Sidney decided, had been nothing short of sacrilege. Now that D'Angelo was gone, no one but Sidney's mom could give him strong enough reason to return. And what if she were to move? He wanted to believe he'd come back to visit Jamal, but would he? No. He would ask Jamal to meet him somewhere instead. Somewhere like Georgetown.

"I would come back," he said, telling himself this statement was true, in a manner of speaking.

Jamal blew air through his teeth. "Yeah, right. But a'ight, let's just say you would. Let's just say that. You come back maybe a few times when you on break and shit, but after a while, after a few months, you wouldn't no more. 'Cause sooner or later it would hit you that you ain't gotta come back." His voice grew subdued. "Shit, if I could get out, I would too."

"You can get out."

In Jamal's eyes flames of aggravation blazed into conflagrations of hatred. Moments passed and the fires smoldered, then died altogether. Jamal looked away, spat on the sidewalk. "I can't get out," he whispered, as if to himself.

"You can!" Sidney yelled, clutching his arm. "I'm telling you, you can!"

Jamal shoved him away. "Would you shut the fuck up? I'm so sick of you sayin' this stupid shit. I can just leave. Fuck kinda shit is that? He was my motherfuckin' brother!"

So loud were Jamal's shouts that Sidney worried Rob's crew had heard. But when he looked their way, they were still making sales, revealing no indication of having heard a word. He was still watching them when he said: "You know if you try anything. . . they'll kill you."

"Look, mind ya business. See, that's the thing. You know 'bout books and shit. You got into Princeton and won scholarships and all that. But right now? Right now you talkin' 'bout shit you don't know a goddamn thing about!"

"Fuck you mean I don't know about it? I was there when it happened. Were you? No. I saw it. He died saving my life. I gotta live with that, and yet I'm trying to move on. Why can't you?"

Jamal stepped away from the van, and suddenly the numbers on his damp jersey were at Sidney's eyes. "You sayin' I should just walk away? And do nothin'? Nigga, I could punch you in yo' face for that."

Sidney clenched his fists, clenched them so tightly he could feel the thin bones in his hands. For a moment he thought he could do it—punch Jamal in the stomach and kick him and drag him to New Jersey tomorrow morning—but then the desire subsided as rapidly as it had surged when Jamal turned away and Sidney recognized, with an aching emptiness, his inability to overpower Jamal physically or mentally. Jamal would die in this neighborhood, and there was nothing Sidney could do.

He could feel himself being dragged down into the reddish whirlpool of what happened to D’Angelo that night last week. He swam, struggling with every tendon in his soul to resist the pull, to dwell on a more benevolent thought, an amusing one. He'd nearly reached the whirlpool's outer lip, but just then he felt himself swallowed, pulled under, and he was there again, with D'Angelo, the two of them striding through pale pools of light spilt by streetlamps. D'Angelo, for some unrevealed reason, was rushing down the hill toward his car, and it was all Sidney could do to keep up. It was all Sidney could do to get responses of any kind from him, let alone answers to questions. Then something struck D'Angelo still, left him rooted to the concrete slab on which they stood.

"What's wrong?" Sidney asked.

D'Angelo said nothing, his eyes—light brown like his skin and lips—fixed on something, their stare accentuated beneath the brim of his green Celtics cap.

"What is it?" Sidney asked. He followed D'Angelo's eyes to the redbrick buildings on the corner up ahead and saw nothing of significance, but what he heard was the roaring of an engine. Hidden from view, a car was racing up the side street toward them.

In a cloud of dust and din a black Maxima fishtailed around the corner, sped up the hill and screeched to a halt in the middle of the street, the engine still running. The car belonged to Junebug, one of the guys in Rob's crew.