by Dana Crum

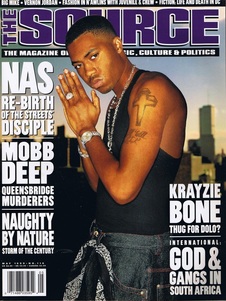

This excerpt from my novel At the Cross was published in The Source in 1999.

For most of the day and much of the evening, rain had pounded down on D.C., wetting but not washing the squalid streets of Carver Terrace; and even now, minutes after the maelstrom had ceased, a turbid rivulet still streamed against the curb, carrying with it cigarette butts, crack vials, golden leaves and ripped condom packages. The moisture had exasperated rather than quelled the heat so that now it was thick and heavy around Sidney, like an unwanted blanket. Soon the sky cracked and shattered again, except this time only a few falling shards made their way to earth. Clusters of them could be seen slanting down in the pale green cones of streetlamps. Sidney remained outside because the moisture felt cool and demulcent on his skin. He didn't know why Jamal, in his silence, remained, and he didn't ask. That Jamal would stand outside even in drizzling rain was all the more surprising given his comment over the phone earlier today. After Sidney noted the city was getting some much-needed rain, Jamal had muttered, "That's just God pissin' on us."

Beneath the light from the streetlamps Jamal's grey Georgetown jersey glistened. His exposed arms, slender but muscular, were crossed, the dark skin freckled with raindrops. As he stared straight ahead, his thin mustache seemed even thinner over his thick unparting lips. Sidney felt pressured to speak, but all his thoughts led inevitably down the paths of college and D'Angelo, so he too remained silent. He wondered if D'Angelo had somehow passed on to Jamal his mercurial, at times aloof personality. Sidney had long believed this night, his last before leaving for college, would be a riotous one where the three of them would reminisce over old times and where he might finally yield to D'Angelo's insistence and for the first time really drink, quaff more than a couple of beers and maybe try Vodka or Jack Daniels or even Everclear. He'd thought he might even smoke some trees with Jamal, who would smoke until there was none left, who, with reddening eyes, would laugh at his own endless jokes even if no one else did. Sometimes Jamal would guffaw before he could even get a joke out. He could keep himself company for hours that way. And he was keeping himself company tonight, but with morbid brooding instead of weed-induced humor. Sidney had imagined himself drinking or smoking too much tonight to occupy his mind so he wouldn't think about what he knew D'Angelo and Jamal were thinking about. But instead only he and Jamal were there; and they were both pondering, though neither had admitted it, Sidney's impending departure. Their minds were further encumbered by an immeasurably worse event that had already occurred.

As Sidney began to remember that event, as he began to remember what had happened to D'Angelo, he twisted a pantsleg of his jeans and stared at Jamal's turned-away face for help. He longed to rip out that huge slab of his cerebrum that held memories. Instead of setting them free to fly away like wild and whirling birds, his greedy brain clutched the most abhorrent memories tighter, as if for its very sustenance.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed